Understanding Parkinson’s Disease & Dementia

The medical community has gradually shifted in its understanding of Parkinson's disease (Emre et al.). Whereas historically, focus was on Parkinson’s as a movement disorder, we now recognize that it affects cognitive functioning. Parkinson’s disease dementia presents unique clinical challenges, especially when it comes to medication management.

From mild cognitive impairment to dementia

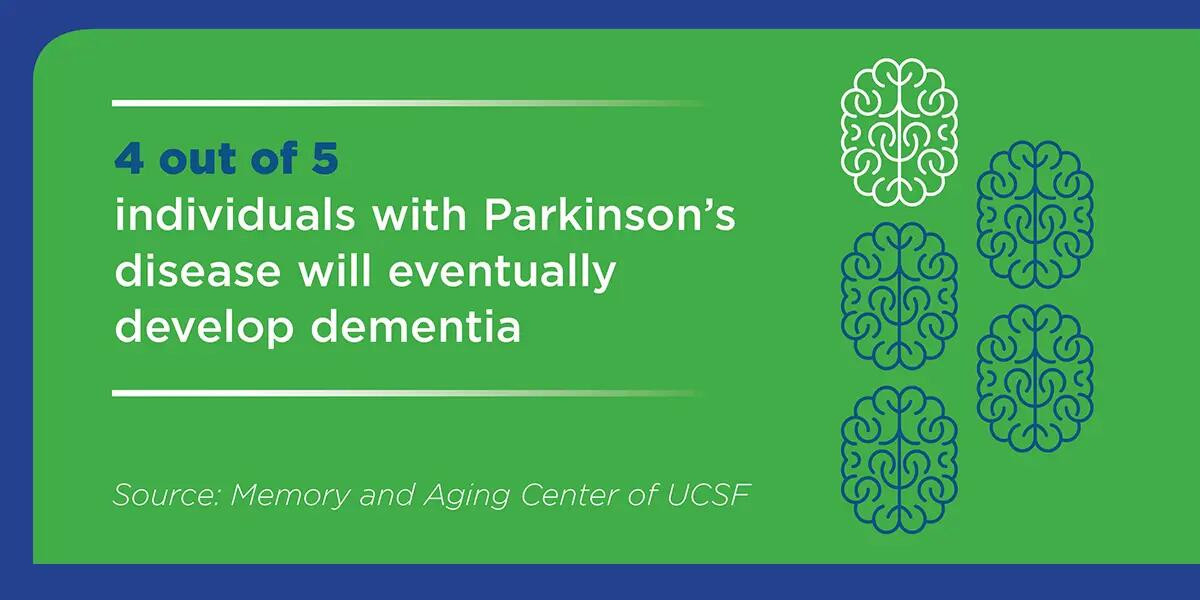

Many patients with Parkinson’s disease develop some form of mild cognitive impairment, which may evolve into dementia. In fact, about four out of five individuals with Parkinson’s’ disease will eventually develop dementia, according to Memory and Aging Center of UCSF. A typical timespan from the time movement disorders begin until occurrence of dementia is about 10 years.

Age is the greatest risk factor for dementia in general (UCSF), with dementia defined as “any disease that causes a change in memory and/or thinking skills that is severe enough to impair a person’s daily functioning.” Advancing age is a factor in risk for progression of Parkinson’s to Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD, G31.20), according to an expert task force. They say, “The incidence of dementia in PD is increased up to six times, point-prevalence is close to 30%, older age and akinetic-rigid form are associated with higher risk.”

Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD)

Hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease are slowed movement, tremor, and instability when walking. Symptoms of PDD may include impairment of memory, attention, executive function, visuo-spatial function, delusions, hallucinations, apathy, depression, anxiety, and excessive daytime sleepiness, according to the task force. UCSF describes sleep disturbances as “REM behavior disorder,” which can lead a person to act out their dreams.

Compared with Alzheimer’s disease, in PDD:

- Irritability and aggressive behavior are less common

- Major depression is more common (expert task force).

In PDD, a majority of hallucinations are visual, not auditory, according to the task force.

The cause of Parkinson’s is unknown, but the pathological correlate is “a large build-up of a protein called alpha synuclein that clumps together to form Lewy bodies,” according to UCSF. Eventually, this leads to the death of nerve cells. UCSF further explains, “Early in PD, the disease process affects parts of the brain important for movement, but as the disease progresses, eventually parts of the brain that are important for mental functions such as memory and thinking become injured.”

Steven Posar, MD, Founder and CMO of GuideStar, describes Parkinson’s disease as “a protean neurodegenerative disorder which is a geriatric disease.” Despite the high profile of people like Michael J. Fox, he explains, only 3% of Parkinson’s disease diagnoses occur in people under age 55. Clinical presentation can be subtle in the old elderly, he adds.

Diagnostic criteria for PDD

A Task Force of the Movement Disorder Society developed diagnostic criteria for diagnosing dementia associated with Parkinson’s (PDD). The presence of Lewy bodies can make differential diagnosis between PDD and Dementia with Lewy Bodies a challenge. Thus, the task force criteria begin with a “core” foundation: First, there must be a validated diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Secondly, there must be a slow progression of dementia symptoms, which would be assessed through patient history, clinical examination, and cognitive measures. The patterns of gradual decline and interference with ADLs are key. These two may point to a “probable diagnosis,” the task force says. Additional diagnostic criteria further explore the pattens of cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms.

Expert neuropsychological assessment is crucial in forming an accurate diagnosis and in following the course of a patient’s dementia, according to the task force. Standardized assessment protocols with validated models, as used by the GuideStar Eldercare team, ensure rigor and consistency in patient care. Our model, based in neurology, ensures proper care and diagnosis, which leads to better quality of care.

Dopamine and medication management for PDD patients

Cognitive and behavioral symptoms in PDD are complex. While medications can help with hallucinations, UCSF also says that “many of the medications used to treat hallucinations may make movement symptoms worse.” Dr. Posar walks through the medication challenge of “a dog chasing its tail clinically” in the presentation, Neurologic Versus Psychiatric Diagnoses in Dementia. Parkinson’s disease depletes dopamine activity in the basal ganglia and substantia nigra, which is why medications that increase dopamine can improve a patient’s movement.

The problem, though, is that the dopamine “goes everywhere,” he explains. This creates higher dopamine levels in the amygdala and can produce psychosis. Sometimes, a clinician will prescribe an antipsychotic, a dopamine receptor antagonist, to address psychotic symptoms. This approach can sometimes lead to a worsening of the Parkinson’s symptoms. The drug approved by the FDA in 2016, pimavanserin, can sometimes get around this issue, says Dr. Posar. In addition, he explains, if psychosis is being driven by medications, sometimes a trial of even a small dopamine adjustment may have a positive impact; it can be a fine balance. The GuideStar medical group of psychiatrists, neurologists, internists, geriatricians, psychologists, and psychiatrically trained nurse practitioners help guide clinical challenges such as these for the long-term care patients they serve.

At this time, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease dementia. Among GuideStar team members, the goal is to ease suffering while actively promoting patients’ safety, functionality and dignity.